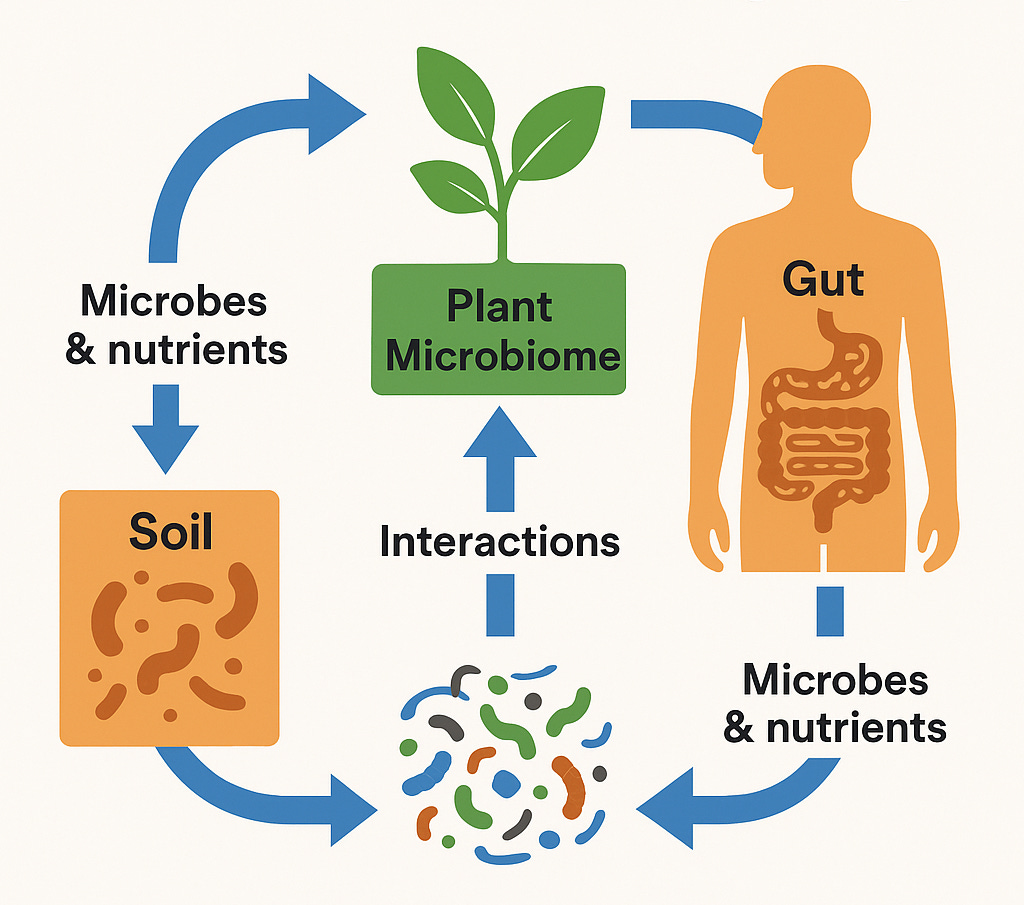

Every bite of food we eat carries more than calories or nutrients. It carries with it microscopic travelers - microbes that originate in soil, find refuge in plants, and ultimately take up residence in our gut. This journey, described by scientists as the soil–plant–gut microbiome axis, is reshaping the way we understand food, health, and the environment.

The invisible web that links dirt to dinner is not just a curiosity for researchers; it has direct consequences for how resilient our farms are, how nutritious our diets become, and how well our immune systems defend us. These microbial connections ignore the boundaries we humans tend to draw, between agriculture and health, between rural and urban, between national borders. Recognizing and nurturing them could redefine how we frame both policy and practice in India and beyond.

The Smallest Players with the Biggest Roles

Microbes are often misunderstood. For decades they were either celebrated as tools of fermentation or demonized as causes of disease. Today, the narrative is shifting. Microbes are being recognized as the hidden infrastructure of life.

In soils, they recycle organic matter, release nutrients, and build the very structure that allows plants to thrive. Without this microbial activity, soils become inert, demanding ever-higher doses of fertilizer to stay productive. Plants themselves are never alone. They host entire microbial communities on their roots, leaves, flowers, and seeds, microbiomes that protect them from pathogens, increase nutrient uptake, and even influence the flavors and nutritional qualities that reach our plates.

Once food is consumed, microbes continue their work inside us. In the gut they ferment dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids that reduce inflammation, regulate metabolism, and provide energy. Some strains are even linked to protection against diabetes, obesity, and certain cancers. In this way, soil fertility, crop resilience, and human health are inseparably tied together through microbial activity.

The Soil–Plant–Gut Highway

This continuum functions like a biological highway. Soil acts as a vast “microbial seed bank,” holding nearly a quarter of Earth’s biodiversity. Plants selectively recruit microbes from this reservoir, and when we eat these plants, many of their microbial partners accompany them into our bodies. Some microbes take root in the gut, others influence health indirectly by producing compounds in plants that serve as prebiotics.

The flow, however, is not always beneficial. Alongside friendly companions like Lactobacillus or Bacillus subtilis, which support health across soil, plants, and humans, harmful organisms such as Salmonella or Shigella can also exploit these routes. Whether this microbial traffic strengthens resilience or spreads disease depends on how carefully we manage soils, farming systems, and food safety practices.

The lesson is stark but hopeful: gut health does not begin in hospitals or pharmacies, but in the soils beneath our feet. The choices made by farmers and policymakers ripple through plants into human bodies, shaping immunity, nutrition, and well-being.

Beyond the Microscope: Why It Matters Globally

Seeing microbes as part of one connected system shifts the way we think about global challenges. In agriculture, they influence whether crops withstand drought, pests, and nutrient stress, while also reducing the dependence on costly chemical inputs. In nutrition, they determine how nourishing our food becomes and how well our gut ecosystems are supported. In public health, they sit at the heart of the antimicrobial resistance crisis, where microbes carry resistance genes from farms to food to hospitals.

Global voices are increasingly calling for microbiomes to be integrated into the One Health framework, which recognizes that human, animal, plant, and environmental health are deeply interconnected. Yet most microbiome research is still concentrated in wealthy countries, even though the richest microbial diversity and the most urgent health and food security challenges lie in the Global South. Without course correction, the benefits of microbiome science will remain skewed toward the privileged few.

The Equity Imperative: Why Low- and Middle-Income Countries Hold the Keys

For countries like India, the microbiome is not an abstract frontier, it is an everyday reality. Our fields, diets, and traditional practices already embody microbial richness. Indigenous farming communities have long sustained microbial diversity through composting, crop rotations, seed saving, and fermentation traditions. These practices are invaluable reservoirs of both microbes and knowledge.

Low- and middle-income countries also face the greatest stakes. They struggle with malnutrition, infectious diseases, climate vulnerability, and AMR hotspots. These interconnected problems make them the very places where microbiome-informed solutions can have the most immediate and transformative impact. To exclude them from the global agenda is not only inequitable but also scientifically short-sighted.

Equity in microbiome science means more than just access to data. It requires investment in local laboratories, the development of benefit-sharing frameworks to prevent exploitation of microbial resources, and co-created research agendas that respect both scientific rigor and cultural traditions. For India, this represents a unique opportunity: to move from being a passive supplier of data for global studies to becoming an agenda-setter shaping the world’s microbial future.

Policy Pathways Forward: Microbiomes in One Health

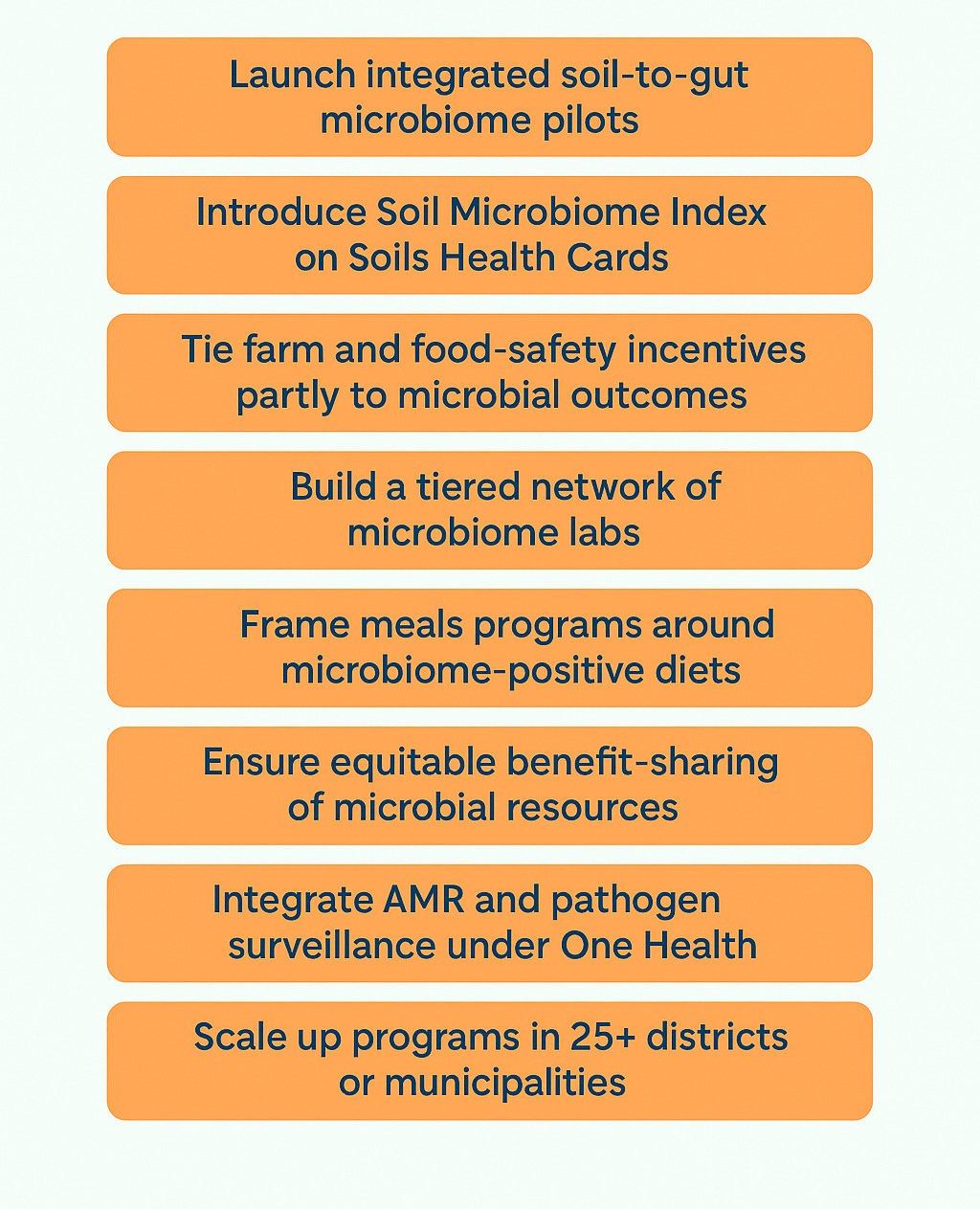

India already has the institutional scaffolding. The challenge is to weave microbiome science into existing missions. The National One Health Mission and the proposed National Institute of One Health in Nagpur provide a strong backbone for integrating soil and plant microbiomes into surveillance systems for AMR, zoonoses, and foodborne pathogens.

The National Mission on Natural Farming can be enriched by adding microbiome indicators - such as a Soil Microbiome Index - to Soil Health Cards. This would give both farmers and policymakers measurable biological signals of soil vitality, beyond chemical parameters. The PM-PRANAM scheme, which rewards states for reducing fertilizer use, could be restructured to also reward improvements in soil microbial diversity and biological outcomes, aligning incentives with sustainability.

On the nutrition front, public programs like the Mid-Day Meal Scheme and POSHAN Abhiyaan can be reframed around microbiome-positive diets. Greater diversity of plant-based foods and safe fermented preparations can support gut health at scale. At the research level, establishing Regional Microbiome Labs in spice belts, millet-growing regions, and peri-urban vegetable hubs would generate the local data needed for both science and policy. At every step, governance must ensure equitable benefit-sharing so that communities and farmers who steward microbial resources share in their value.

Everyday Connections: What It Means for You and Me

While microbiomes can seem like a distant subject of advanced science, their relevance is intimate and immediate. For families, food choices that include a variety of fruits, vegetables, pulses, and traditional ferments nurture gut diversity. For farmers, practices like composting and crop diversification rebuild microbial life in the soil, reducing dependence on expensive inputs. For policymakers, integrating microbial indicators into routine monitoring can transform agriculture and health from reactive systems into preventive ones. For researchers and innovators, the soil–plant–gut axis represents a frontier that is both deeply local and globally significant, offering scope for new diagnostics, bio-inputs, and community-driven science.

In other words, microbes are not confined to laboratories. They are present in the farms we cultivate, the meals we prepare, and the bodies we inhabit. Recognizing this gives every actor, from farmer to policymaker, a role in building resilience.

Closing Reflection: Microbiomes Without Borders, Policies Without Silos

Microbes ignore borders, yet our policies remain divided—agriculture in one ministry, health in another, environment in yet another. The soil–plant–gut continuum shows us that these divisions are artificial. The future demands governance that is integrated, evidence-based, and equitable.

By embedding microbiome science into existing frameworks - soil health missions, nutrition schemes, AMR surveillance, and climate adaptation programs - India can strengthen its soils, secure its food, and improve public health. More importantly, it can position itself as a global leader in microbiome-informed One Health policy, setting an example for other low- and middle-income countries.

The invisible web from dirt to dinner is already here. The choice is whether we let it unravel through neglect, or nurture it as the foundation of a healthier and more sustainable future. Microbiomes without borders demand policies without silos.

Further Reading

Fontaine, F., & Callens, K. (2025). Microbiome science for agri-food systems transformation and One Health: Why LMICs must be at the center. Frontiers in Science, 3, 1668866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsci.2025.1668866

Ma, H., Cornadó, D., & Raaijmakers, J. M. (2025). The soil–plant–human gut microbiome axis into perspective. Nature Communications, 16, 4791. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62989-z

Banerjee, S., & van der Heijden, M. G. A. (2023). Soil microbiomes and One Health. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 21, 6-20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00779-w.

Singh, B. K., Yan, Z.Z., Whittaker, M., Vargas, R., & Abdelfattah, A. (2023). Soil microbiomes must be explicitly included in One Health policy. Nature Microbiology, 8, 1367-1372. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-023-01386-y

What a fantastic and eye-opening article! The way you’ve connected soil, plants, and our gut health really struck a chord with me. For the past 10 years, I’ve been reading and researching about the microbiome and its impact on human health, and I couldn’t agree more with how urgent this topic is.

Gut health doesn’t just start in our bodies—it truly begins in the soil beneath our feet. If we don’t integrate this understanding into both health and agriculture right away, we’ll be facing a tsunami of chronic diseases in the coming years.

Thank you for writing this so beautifully—it reinforces why I’ve been so passionate about this subject, and why we all need to start seeing microbes as the invisible thread linking our food, farms, and future health.

Let’s hope policymakers, researchers, and communities act on this knowledge soon—because the future of our health really does depend on the health of our soils.